Git happens: resolving merge conflicts for machine learners, and stashing uncommitted changes

Dealing with merge conflicts, and how to stash changes when you're not yet ready to commit your code.

Hello fellow machine learners,

Last week, we introduced Git for version control and described exemplar scenarios for its utility within the context of machine learning. Before reading on, make sure you’re comfortable with adding, committing, pushing, pulling and local/remote repositories.

Believe it or not, there’s actually a lot more to Git than what we discussed last time. So this time around, we’ll discuss more common Git commands that you may have to use when navigating your projects. In particular, what to do when faced with the dreaded merge conflict, as well as discussing situations where you may need to switch branches even when you’re not yet ready to push your code.

Let’s get to unpacking!

Merging into the master branch

As discussed last week, the master branch represents the most up-to-date working version of your code. So when you’ve tested a feature in one of your developmental branches, you’ll want to merge the desired files back into the master.

Let’s say you want to merge the contents of dev_branch back into the master branch. Assuming you’re synced up with the remote repo, switch over to the master branch with

git checkout masterand merge into it with

git merge dev_branchGit should be able to merge the code in for you automatically. If so, you still ought to read over the changes made in case the code has been merged in an unintended way. However, most of the time you’ll receive an error.

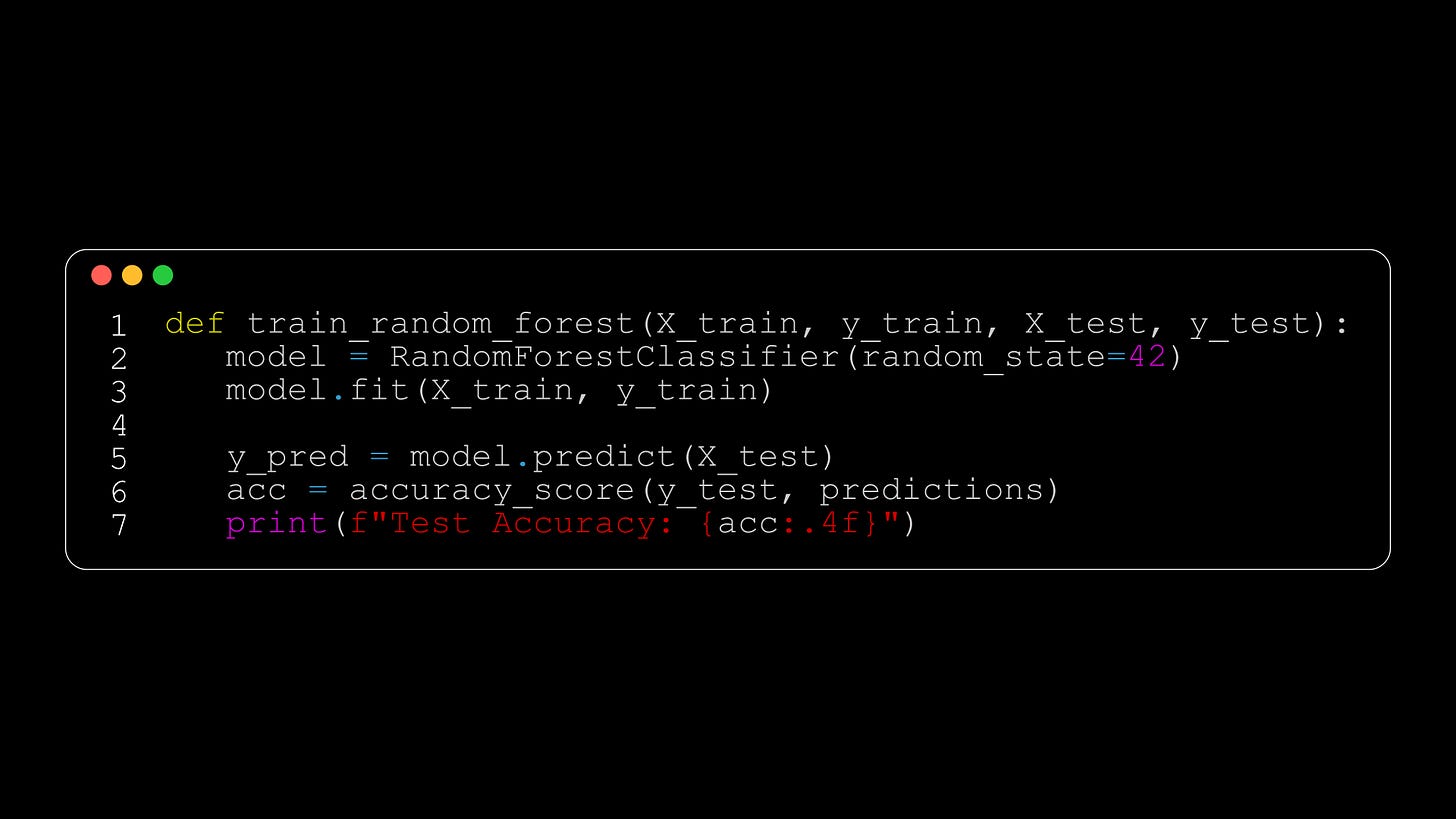

For example, suppose you write a Python function to train a random forest classifier. In the master branch, the code implements a basic random forest like

At this stage, you want to improve the model by tuning its hyperparameters. You create a new branch called feature/gridsearch and implement the code in there:

After testing it yourself, you’re happy with how it works and wish to merge this back into the master branch. But when you try running the relevant merge command in the terminal, you are met with an error like

$ git merge feature/gridsearch

Auto-merging train_model.py

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in train_model.py

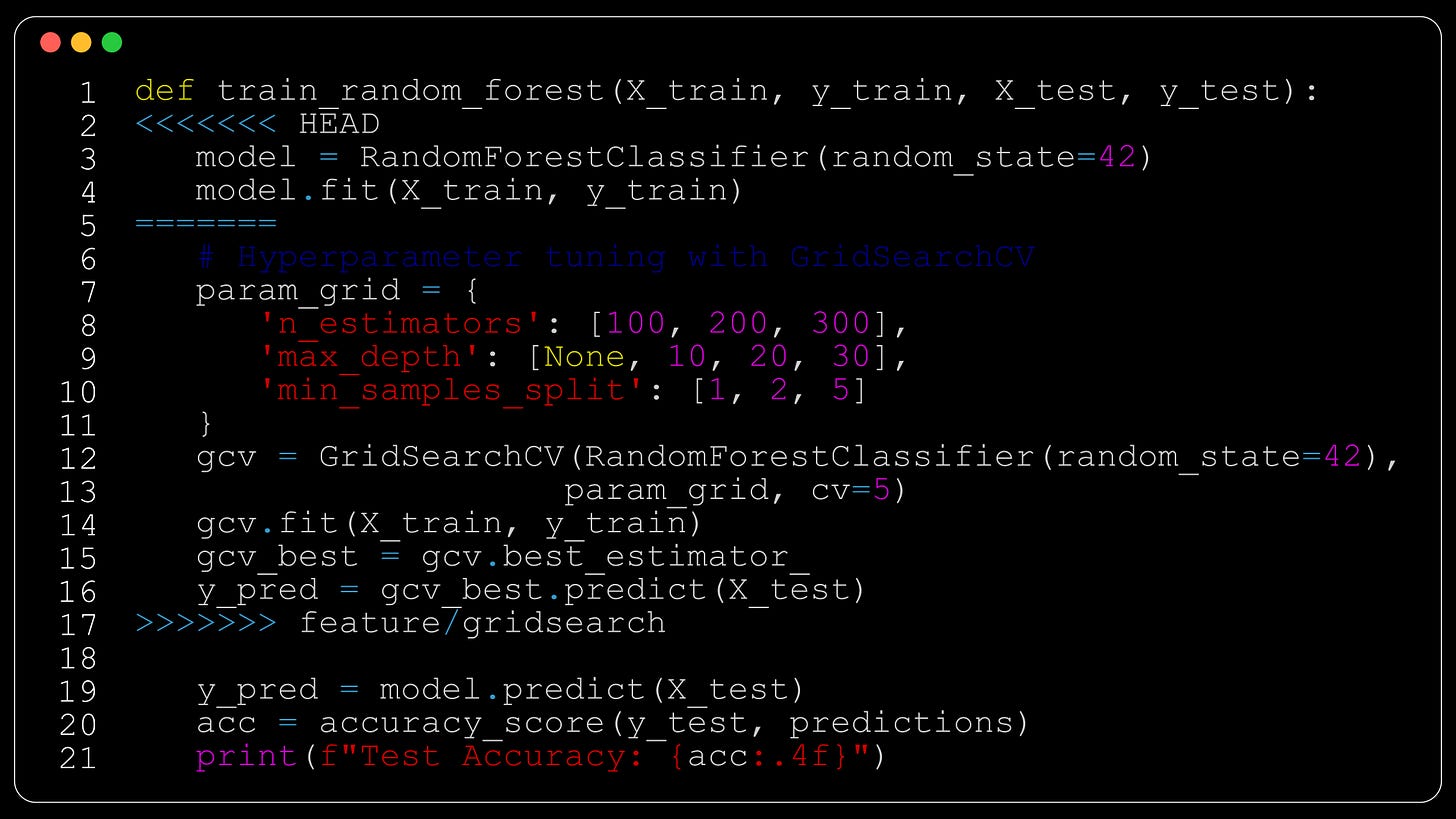

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.Git is confused about how to combine the code in the feature branch with the code currently in the master branch, so we’ll have to give it some help. Depending on the platform you’re using to resolve conflicts, you’ll probably see conflict markers, such as in the following example:

The code between the markers <<<<<< and ===== is the code that’s already in the master branch, and the code between ===== and >>>>>> is the code from the feature/gridsearch branch that we want to merge in.

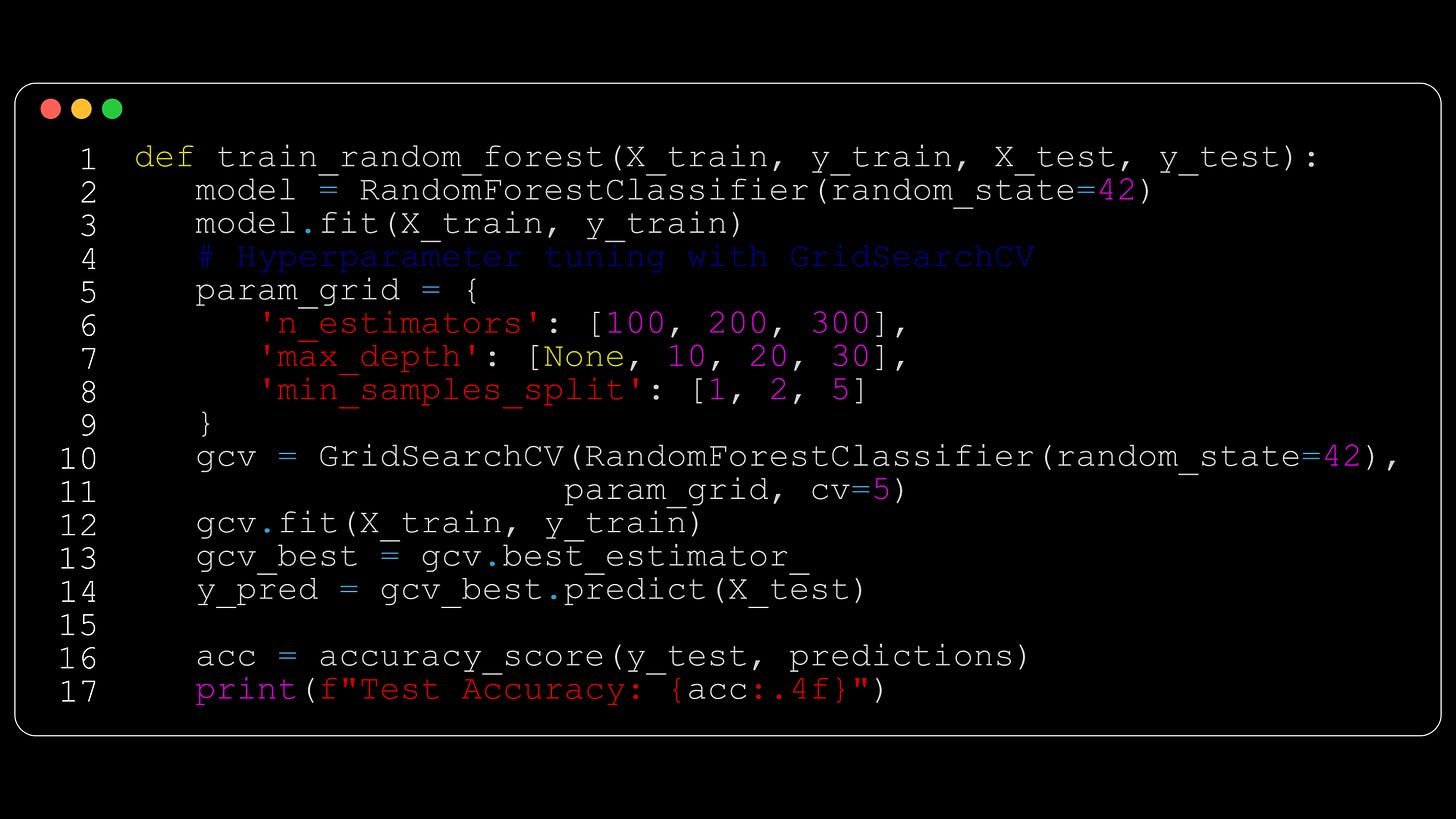

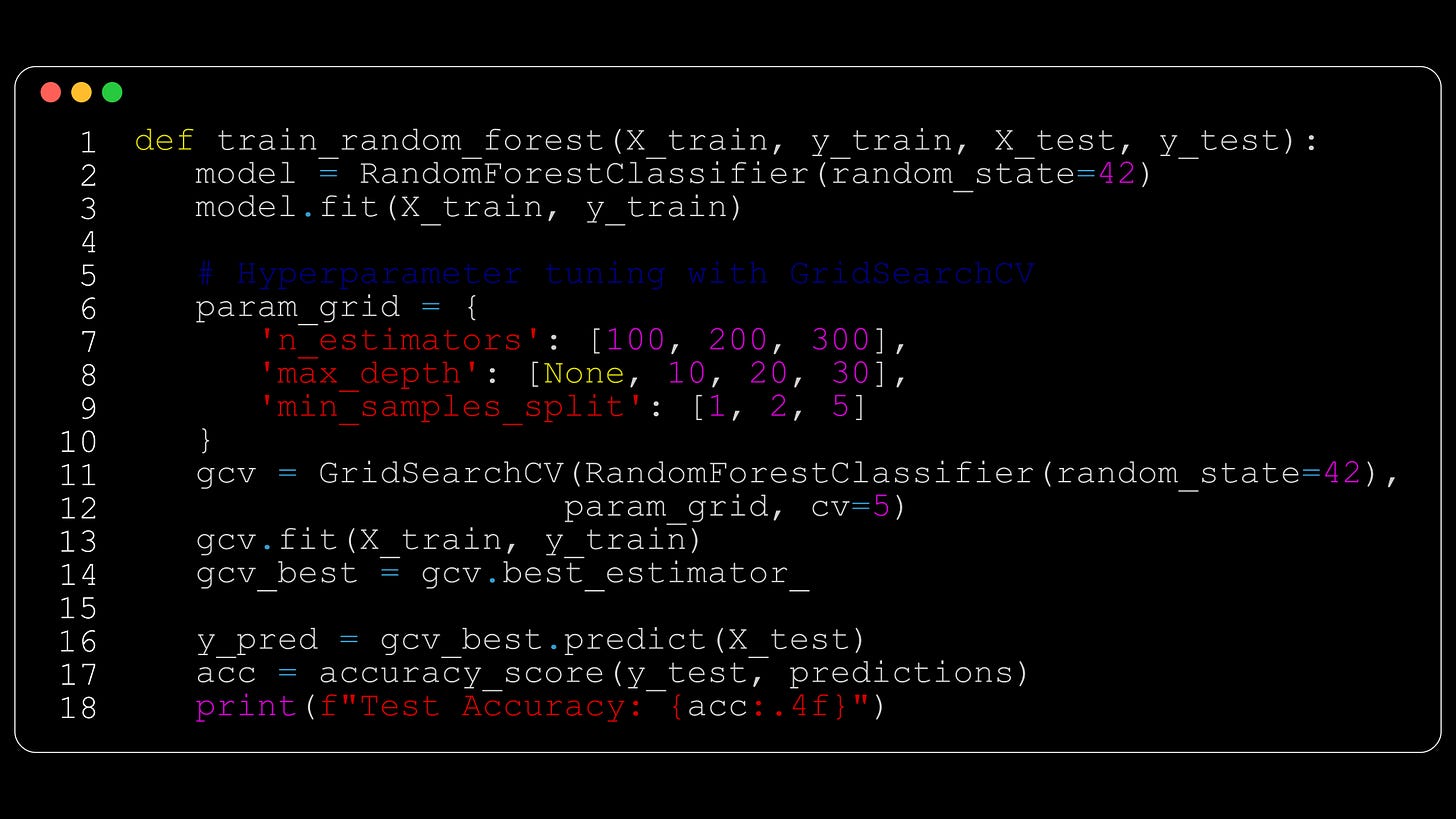

In this example, the only thing we have to be careful about is how the value of y_pred is assigned. We can resolve the conflict by picking and choosing the bits we want to keep, as follows:

Once you’re satisfied, you will have to add and commit the file(s) again for the merge to be successfully registered.

For simple projects, it shoudn’t be too hard for you to pick which of those two you want to keep. But as you might imagine, this process isn’t as simple when there are multiple changes across multiple files in play. To that end, it’d be a good idea to make commits at sensible moments. Rather than pushing all your code at the end of each day, push the changes relevant to one feature in one go, then turn your attention to the next feature and repeat. That way, you should be able to merge features into the master branch one at a time, making any conflicts easier to resolve in isolation. As with anything in computer science, it’s always best to break large processes down into smaller, more manageable steps.

🚨 IMPORTANT POINT 🚨

The conflict markers are added directly into your code. So if you’ve manually resolved an individual conflict, then you will need to delete these markers yourself. I resolved my first merge conflict a few months back (directly on GitLab rather than a in an IDE like VSCode) and didn’t realise this. So when I next ran the master I got a bunch of syntax errors 😅 Learn from my mistakes!

Two people pushing to the same branch

Imagine that you and a fellow ML engineer are working on the same branch of a project. You have both pulled from the remote repo and are working on the same file in the code base.

Suppose further that your friend pushes their changes to the same branch before you do. What do you think will happen if you try to push your changes after?

💭

💭

💭

In this case, your push will fail. Git looks at the ancestry of a branch to determine whether or not to approve a push request. Since Git cannot see evidence of your friend’s recent commit in your local branch’s history, it will prevent you from pushing.

It might seem annoying, but this blockage is a good thing. If it didn’t happen, then we’d end up with two different versions of the code in the same branch, and that would defeat the purpose of version control (not to mention confusing everyone involved).

You can solve this problem by first pulling the code from the remote repo of that branch. This may require you to resolve a merge conflict, which we went through in the previous section. Once this is done though, you’ll then be able to push your work to the local repo.

Another solution would be for you to push your changes to a different branch entirely. But don’t do this just to get out of having to pull and potentially resolve conflicts; adding a new branch should be an intentional choice, say, for the sake of testing a new feature. Otherwise, you wouldn’t be following best practice 😤😤

Switching branches without committing beforehand?!

Here’s another scenario you might find yourself in: you’re currently knee-deep in dev_branch when all of a sudden someone finds a bug in the master branch that needs to be fixed ASAP.

If you try to switch to the master branch without committing your changes to dev_branch, then Git will get unhappy and won’t allow you to swap over. This is because your non-committed code would otherwise be floating around in unstaged-code-purgatory and Git wouldn’t know where to put it.

But you’ve been given a high-priority task to complete in the master branch- what if you just don’t have time to get the code ready for a commit? Perhaps you need some time to work out a bug in this branch, or you want to wait until you’ve completed your current set of analysis so that the commit is more meaningful.

Fortunately, you are allowed to stash any staged files in dev_branch, switch over to the master branch, fix the bug, then switch back to dev_branch and recover the stashed code.

To stash a set of files, first add them to the staging area and then you can run (you might have guessed it:)

git stashThe stash command makes it so that your local repo temporarily matches the remote repo of that branch, allowing you to switch without incurring any error messages. This staged code is stored elsewhere until you choose to retrieve it. If you run

git stash popthen the stashed code will be inserted back on top of the branch that you’ve currently checked out.

Now, if conflicts exist between your stashed code and the branch you’re currently working on, then the git stash pop command will fail and your work will remain stashed.

One way to fix this is to pop the stash on a separate branch (you could make a new branch for this) and then merge this branch back into the original branch, resolving conflicts as needed.

Packing it all up

I hope that this article has helped you better understand the landscape of version control. Here’s the usual roundup:

💪🏼 You may have to manually resolve conflicts when trying to merge feature branch code back into the master branch.

💪🏼 It is far better to make smaller, more meaningful commits that involve the implementation of one specific feature, rather than lumping loads of unrelated code changes together in the same commit. This will help make it easier to merge your code into the master branch, and will make it easier for other project members to understand what was changed in the code and when via the commit message history.

💪🏼 If you need to switch branches when you’re not yet ready to commit your code, you can instead stash the changes, switch branches, and then switch back and pop the stash to get back to where you were before.

Training complete!

I hope you enjoyed reading as much as I enjoyed writing 😁

Do leave a comment if you’re unsure about anything, if you think I’ve made a mistake somewhere, or if you have a suggestion for what we should learn about next 😎

Until next Sunday,

Ameer

PS… like what you read? If so, feel free to subscribe so that you’re notified about future newsletter releases:

Sources

My GitHub repo where you can find the code for the entire newsletter series: https://github.com/AmeerAliSaleem/machine-learning-algorithms-unpacked